Stories in the Maps

Within each line that draws connections between Villa Alta’s native communities and legal agents in nearby and distant locales lies a story: a land dispute between native communities, a decision to transfer property, or a desire to obtain a right or privilege (fig. 8). The maps allow us to see each authorization of power of attorney as a web of relationships among people, places, and institutions in which patterns emerge and individual connections stand out. In this regard, the maps are a tool as much as an end: they allow us to see data in a new way, and to ask questions that send us back to the archive to reconstruct the stories within the maps.

When we scrutinize the maps and Gephi model for eighteenth century Villa Alta, some broad trends emerge. Within Villa Alta itself, there is a dense web of connections among communities, indicating the instances in which native municipal officers gave power of attorney to unlicensed indigenous legal agents (or legal entrepreneurs). These connections are discernible only if zooms into the region itself. When one zooms out, the density of lines connecting the region to Oaxaca City and Mexico City immediately catches the eye. When one zooms out even further, the most dramatic set of connections clusters between all of the native villages of the region and Madrid. What kinds of conflicts, desires, needs or impulses generated connections within the district of Villa Alta on one hand, and between the villages of the district and Madrid?

These questions sent me back to the data and then back again to the letters of attorney upon which this project rests, allowing me to reconstruct some of the vital stories within the maps. This detective work led in a number of directions, including other archival materials because the legal business for which a letter of attorney was generated often materialized in a legal case and its related documentation. It also led to other kinds of primary materials such as royal decrees or to secondary literature that details the legal business in question.

Of the stories within the maps, I would like to highlight two instances in which multiple indigenous towns granted power of attorney to very different kinds of legal agents for very different kinds of legal business. In the first, dated 1744, eleven towns – Lalopa, Yagallo, Lachichina, Yaviche, La Olla, Yatoni, Talea, Juquila, Yatao, Cacalotepeque, and Tanetze — from the Northwest corner of the Villa Alta district (Nexitzo Zapotec) gave power of attorney to don Antonio de Aldas, a native principal (local notable) and resident of San Juan Tanetze, a parish seat and administrative center. Aldas happened to be the maestro de escuela (school master) for the parish, meaning that he taught Spanish and the Christian doctrine to native parishioners, and worked closely with the parish priest.

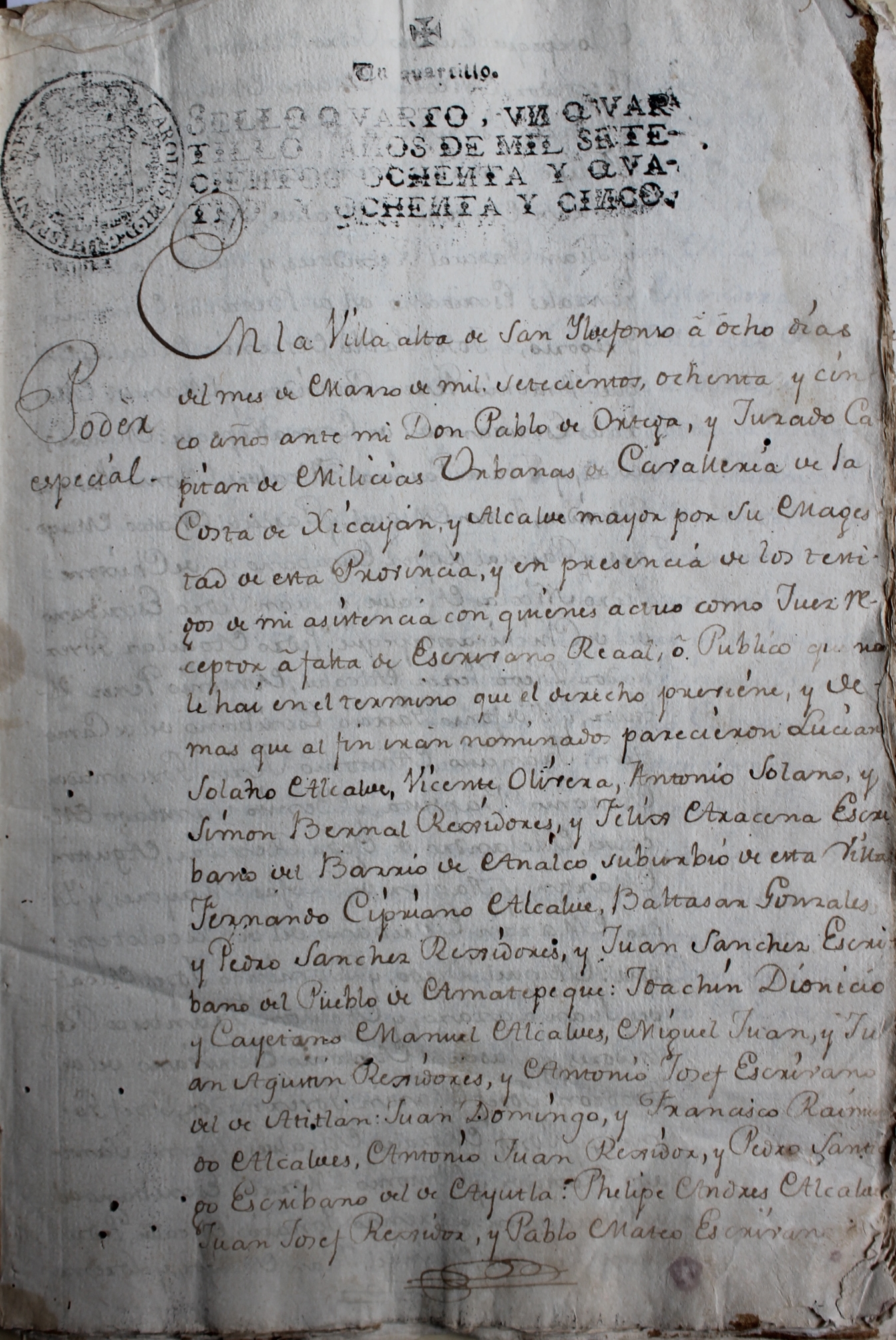

The letter of attorney signed by the eleven communities was a poder especial that authorized Aldas to contradict in court the claim on the part of the officials of the town of San Juan Yaée to the exclusive right to host the local market (tianguis) (fig.9 and 10). According to the letter of attorney, Yaée’s authorities had obtained a Real Provisión – a legal order given by the Audiencia of Mexico (akin to the Supreme Court of the viceroyalty) on behalf of the King – that upheld Yaée’s claim to host the market. The eleven towns directed Aldas to request the rescindment of the Real Provisión and to pursue a resolution favorable to their communities, which presumably meant that one of the plaintiff towns could host the local market.[1]

The legal dispute for which this letter of attorney was authorized formed part of a larger conflict between the granting towns and the town of San Juan Yaée regarding whether San Juan Yaée or San Juan Tanetze was the legitimate parish and administrative seat (cabecera), and what forms of labor and resources the granting towns who were subject to the cabecera’s authority owed to it (fig 11, 12, 13). One of the privileges that often accompanied cabecera status was the right to host the local market. The San Juan Yaée-San Juan Tanetze dispute over cabecera status and other related privileges began in the 1690’s and continued until the 1760’s — through a series of legal cases in the district court of Villa Alta, the ecclesiastical court of Antequera (Oaxaca City), and the Real Audiencia of Mexico City. This ongoing litigation must be understood against the backdrop of changes in the region over the course of the eighteenth century: demographic growth, increasing pressure on land and resources, and administrative change, all of which fostered competition among the region’s communities. San Juan Yaée and San Juan Tanetze and its allied plaintiff towns hired many legal agents near and far, indigenous and non-indigenous, to represent their interests and shepherd the individual cases through to their conclusion. Aldas was likely granted power of attorney for this aspect of the case because of his identity as a high-status indigenous resident of the town of San Juan Tanetze, position as schoolmaster, literacy in Spanish, and intimate knowledge of the customary relationships among the towns of the region.[2]

Contrast this 1744 contract, which was primarily local in its significance, to another letter of attorney dated 1785, which accounts for the lines connecting all ninety-four native towns in the district of Villa Alta to Madrid. The story within the map can be traced to the late eighteenth-century reforms of Spain’s Bourbon monarchy. Grounded in the principles of enlightened absolutism, the Bourbon Reforms represented a wide-ranging attempt to modernize the Spanish Empire, especially its administration and economy. Four major Bourbon objectives came together in this 1785 letter of attorney: to re-open the spigot of resources and revenue flowing from the colonies to the imperial treasury; to pay back Spain’s colossal debt from its wars with European rivals; to privatize corporately held property, including that of the Church and the communal treasuries of native towns (cajas de comunidad); and to create a national bank of Spain.[3]

In many ways, the last of these objectives – the establishment of the Bank of San Carlos by royal decree of Charles III in 1782 – was a product of the first three. The foundation of the national bank, a symbol of and tool for the rationalization of Spain’s finances, grew out of Enlightenment economic philosophy. The Bank of San Carlos was intended to stabilize Spain’s credit, increase the circulation of money in the empire, and facilitate commerce. The bank’s initial investments went toward paying off the debts that the imperial army had accrued over many decades of warfare.[4]

One of the first questions confronted by the bank’s founders was: who would finance it? Wealthy Spaniards and Frenchmen were early investors, but the Crown looked across the ocean to its American holdings to seek further financing. In addition to the wealth of prominent Mexican creoles, the treasuries of Indian communities in some regions of New Spain – including Oaxaca – provided a key source, making Indians unlikely shareholders of Spain’s new national bank.

José de Gálvez, Inspector General of New Spain from 1764-1772, and minister of the Council of the Indies from 1775-1787, played a key role in drumming up capital in New Spain for the Bank of San Carlos. Taking Gálvez’s cue, don Ramon Posada, minister in charge of civil administration in Mexico (fiscal de lo civil), sought to convince Mexico’s Indian communities to buy shares in the bank. He sent an edict to the governors of Mexico’s many provinces extolling the virtues of the bank and soliciting investment, which in turn they circulated to the Indian communities of their regions. There were no takers. Undaunted, Posada turned to more coercive measures, demanding audits of Indian community treasuries, and requiring “unproductive” funds to be dedicated to buying shares in the Bank. The Audiencia of Mexico opposed Posada, arguing that the Indians should be at liberty to choose whether or not to finance the bank. Their position was grounded in the Audiencia’s long-held pretension to be the “protector” of Indians; ultimately, the appeal to respect the Indians’ liberty won the day. The provincial governors (alcaldes mayores) were to gather the Indian governors of their regions and explain to them the benefits of investing in the bank. It would be up to the Indian governors to convince their municipal authorities whether to buy shares or not.[5]

Nominal respect for the Indians’ free will did not guarantee an absence of coercion. Though powerful, Indian governors were not the equals of their Spanish overlords; the alcaldes mayores of New Spain punished or removed Indian governors who fell short of delivering tribute or goods that they owed through the forced system of production known as the repartimiento. At the same time, the Spanish king was an important symbol in New Spain’s Indian communities. He represented a benevolent if distant sovereign who was supposed to protect the interests and welfare of his indigenous subjects against the predations of local Spanish officials. It is therefore possible that Indian governors and municipal authorities might have viewed investment in the bank through the lens of loyal vassalage to the Crown, opting for it as a symbol of their loyalty. They may also have been convinced by economic arguments, or felt coerced by the alcalde mayor. Whatever their motivations, if native authorities decided on behalf of their communities to buy shares, the edict made clear that they had to give power of attorney to Don Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, a Spanish aristocrat, statesman, judge, intellectual, and close associate of one of the founders of the Bank of San Carlos, Francisco Cabarrús. The communities would have to pay for the transport of their investment in specie to Spain, where Jovellanos would invest it in the Bank, and represent their interests.[6]

That Jovellanos served as legal agent for New Spain’s indigenous investors followed an ironic logic. Jovellanos was an active participant in Enlightenment debates on economic matters, and an admirer of Adam Smith and English economic thought. He wrote a treatise on Spanish agriculture, Informe sobre el expediente de la ley agraria, which he completed in 1784, and finally published in 1795. The treatise advocated the disentailment of Church property and communal lands in Spain, arguing that they hindered agricultural productivity and deterred private investment. Although Jovellanos’ proposals were not implemented in Spain, his ideas traveled across the Atlantic and influenced advocates for land reform in New Spain such as Bishop Manuel Abad y Queipo.[7] In short, Jovellanos, who was charged with the responsibility of representing the interests of indigenous investors in the Bank of San Carlos, also provided fodder for the dissolution of the material basis of their communal identity and political semi-sovereignty.

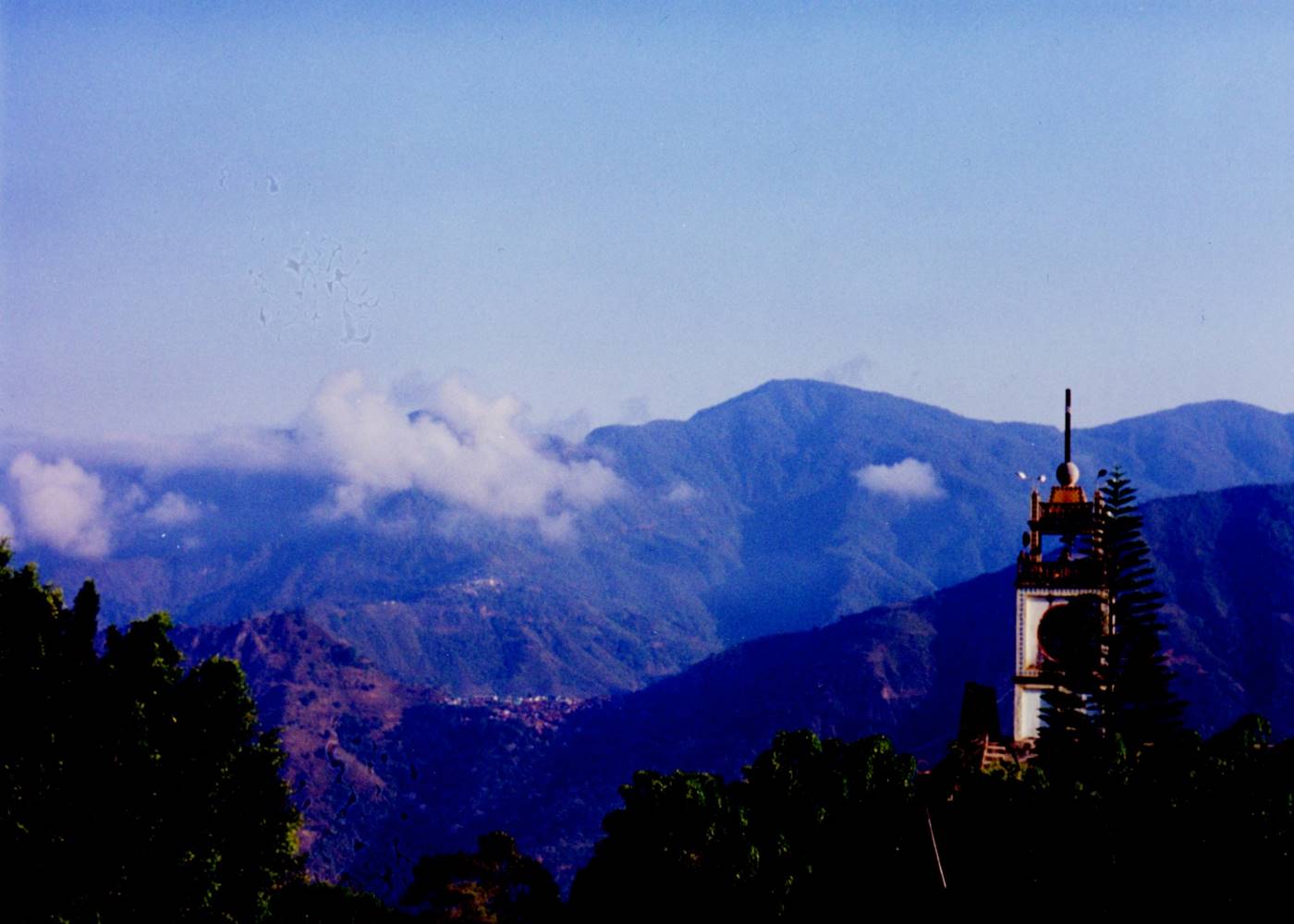

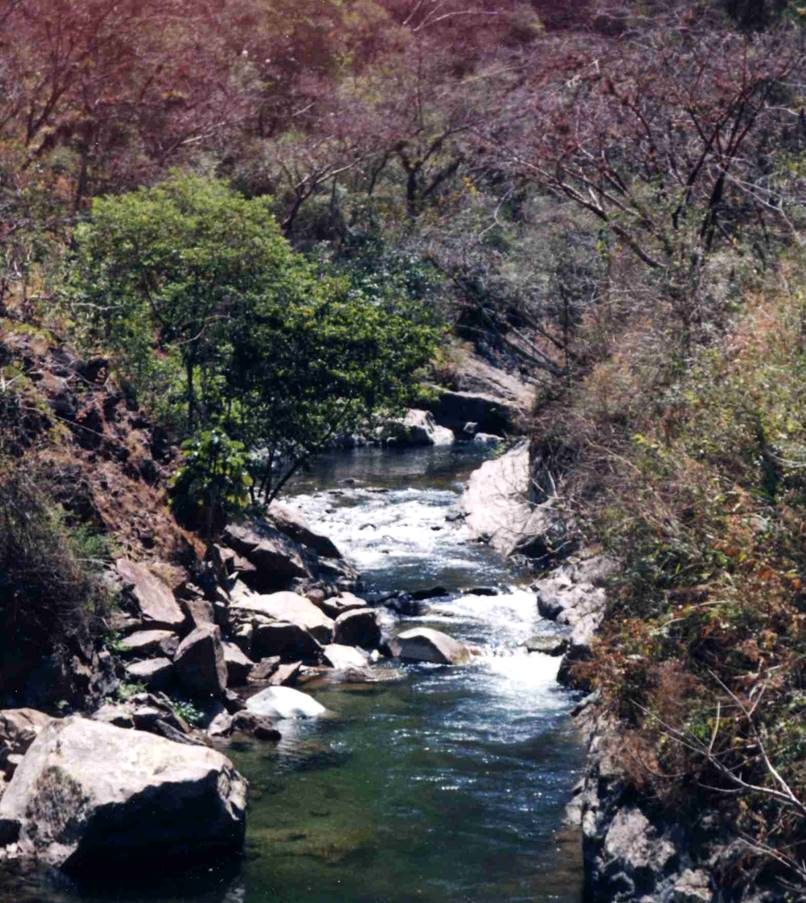

In 1785, the municipal authorities of all 96 communities in Villa Alta brought a total of 27,700 pesos to the alcalde mayor for investment in the Bank of San Carlos, and signed a letter of attorney empowering Jovellanos as their legal representative (fig 14). Given what we know about the geography of the region, this was no small feat. Imagine the municipal officers of ninety-six villages – representatives of five different ethno-linguistic groups – traversing rugged mountains and fording treacherous rivers to deliver a portion of the wealth of their municipal treasuries to the Spanish magistrate for eventual transport across the Atlantic Ocean to Spain (fig 15, 16, and 17). Villa Alta was one of twelve Indian jurisdictions in New Spain to invest in the Bank of San Carlos. The combined investment of its communities was by far the most substantial among the twelve jurisdictions, and over double that of the second largest investment by an Indian district (table 2). This was likely the result of the wealth held in the community treasuries (cajas de comunidad) of Villa Alta’s native towns relative to other districts in New Spain due to the persistence of Indian landholding in the region and in Oaxaca more broadly.[8]

It would be worth researching what if any returns the Indian communities who invested in the Bank of San Carlos received on their investments. The bank faced uncertainty with the collapse of the Spanish monarchy following the 1807 invasion of the Iberian Peninsula by Napoleon Bonaparte and the usurpation of the Spanish throne by his brother, Joseph Bonaparte. During Spain’s brief constitutional interregnum from 1812-1814, the Cortes of Cádiz (Spain’s first national assembly) sought to return the investments to the communities, but was thwarted by the restoration of Ferdinand VII to the throne in 1814, and the onslaught of Mexico’s wars of independence. The shares were reinvested in 1829 into the newly formed successor of the Bank of San Carlos, Banco Español de San Fernando.[9] The story of indigenous investment in the Bank of San Carlos effectively ends with an outright transfer of wealth from Mexican native communities to Spain.[10]

These two stories in the maps provide different but related views of power of attorney in native communities in eighteenth-century Mexico. Native legal activity was varied and layered, involving local political, economic, and religious disputes, as well as matters of imperial scope. Necessarily, native strategies for securing legal representation were multiple, involving legal agents who resided in their own or nearby communities, spoke their languages, and knew first-hand of local custom. At the same time, native strategies involved Spanish noblemen and men of middling origins who were titled lawyers or legal paraprofessionals (agentes de negocios) residing in the district seat of Villa Alta, Antequera, Mexico City, and even Madrid. Don Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos was exceptional in his notoriety; not only was he an intellectual and player at the Spanish court, but he and many of the key figures in the establishment of the Bank of San Carlos were also the subjects of paintings by Francisco Goya, one of Spain’s most renowned artists (fig. 18).[11]

The relationships created by power of attorney put into motion flows of knowledge, power, and resources that spanned mountains, rivers, and even the Atlantic Ocean. When it came to resources, the flow was predominantly outward from native communities to the coffers of legal entrepreneurs and professionals, and legal institutions, although knowledge of the legal system and favorable legal decisions, some of which enriched native individuals and communities, did flow back. Ultimately, native access to Spanish courts – facilitated by power of attorney – pulled native communities into the gravitational orbit of Spanish power, and insinuated law into the fabric of everyday life in some of Mexico’s most remote Indian regions.

[1] AGN Tierras, vol 2771, exp.8 (1743), 6 fols. “Expediente formado a pedimento del comun y naturales del pueblo de San Juan Yaee de la jurisdicción de la Villa Alta sobre el tianguis que se hace en dicho pueblo”; AGN Tierras, vol 2771, exp. 10 (1744), fols. 0-44v, “Autos que siguen los naturales de los pueblos de San Juan Taneche y otros de la jurisdicción de la Villa Alta con el comun de los naturales de los pueblos de San Juan Yaee de la misma jurisdicción sobre la celebración del tianguis y mercado.”[2] Yanna Yannakakis, The Art of Being In-Between: Native Intermediaries, Indian Identity, and Local Rule in Colonial Oaxaca (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008), ch.3; “‘Costumbre,’ A Language of Negotiation in Eighteenth Century Oaxaca” in Ethelia Ruiz Medrano and Susan Kellogg, editors, Negotiation within Domination: Colonial New Spain’s Indian Pueblos Confront the Spanish State (University Press of Colorado, 2010), 137-171.

[3] The historiography on the Bourbon Reforms is extensive. For a wide-ranging recent work in English, see Allan J. Kuethe and Kenneth J. Andrien, The Spanish Atlantic World in the Eighteenth Century: War and the Bourbon Reforms, 1713-1796 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

[4] Earl Hamilton, “Plans for a National Bank in Spain, 1701–1783” Journal of Political Economy 58 no. 3 (1949): 315-336; Pedro Tedde, El Banco de San Carlos (1782-1829) (Madrid: Banco de España; ALianza Editorial, 1988). Published primary sources on the establishment of the Bank of San Carlos include: Don Matias De Galvez … Virrey … De Nueva España … : Deseoso S.M. De Proporcionar En Lo Posible Á Sus Fieles Vasallos Todos Los Arbitrios Conducentes Al Mas Seguro Y Corriente Giro De Sus Respectivas Dependencias, Se Ha Dignado Erigir Un Banco Nacional … Baxo De Las Reglas Prescritas Por Su Real Cédula De 19 De Julio De 1782, Cuyo Tenor Es El Siguiente (Mexico: publisher not identified; 1782); Real Cedula De S.M. Y Señores Del Consejo, Por La Qual Se Manda Guardar Y Cumplir El Real Decreto Inserto, En Que Se Declara Que Todos Los Caudales Pertenecientes Por Qualquier Título, Y Que Deben Imponerse Á Favor De Mayorazgos, Cofradías, Capellanías, Hospitales Y Obras Pias, Pueden Emplearse En Acciones Del Banco Nacional De San Cárlos, Y Se Han De Considerar Su Capital Y Réditos Como Parte De La Propiedad De Los Vínculos, Ó Fundaciones, Á Que Correspondan (En Madrid: En la Imprenta de dodro Marin. Spain, and Pedro Marín, 1783); Real Cédula De S.M. Y Señores Del Consejo, Por La Qual Se Crea, Erige Y Autoriza Un Banco Nacional Y General : Para Facilitar Las Operaciones Del Comercio, Y El Beneficio Público De Estos Reynos Y Los De Indias, Con La Denominacion De Banco De San Cárlos, Baxo Las Reglas Que Se Expresan, Van Añadidas Las Modificaciones Hechas Á Esta Real Cédula En Virtud De Reales Órdenes Posteriores, Y De Los Reglamentos De Las Oficinas Del Mismo Banco Aprobados Por S.M. (Madrid: Imprenta de la viuda de Ibarra; Banco de San Carlos, 1786); Quarta Junta General Del Banco Nacional De San Cárlos, Celebrada En La Casa Del Mismo Banco El Dia 29 Diciembre De 1785. (Madrid: En la impr. de la viuda de Ibarra, hijos y compañía) http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/MOME?af=RN&ae=U108203047&srchtp=a&ste=14&locID=mlin_m_tufts

[5] José Antonio Calderón Quijano, El Banco de San Carlos y las comunidades de indios de Nueva España (Sevilla: Banco de España, Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos, 1963); 27-31.

[6] Ibid, 32-34.

[7] D.A. Brading, The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriot and the Liberal State 1492-1867 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 507-598.

[8] “Nota de los caudales que debe existir en las Caxas de Comunidad en las jurisdicciones sugetas a esta Contaduria General (de la Nueva España), según las cuentas remitidas por los respectivos justicias, deducidas y a las cantidades que de estos fondos se impusieron en el Banco Nacional de San Carlos, y las que igualmente se erogaron en otros gastos indispensables en virtud del superior permiso.” AGN, Intendencias, t.3, 1783-1785, fs. 188-192, cited in Carlos Sánchez Silva, Indios, comerciantes y burocracia en la Oaxaca poscolonial, 1786-1860 (Oaxaca, México: Instituto Oaxaqueño de las Culturas; Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca, 1998), 67-68; Calderon Quijano, El Banco de San Carlos, 62-72.

[9] Ibid, 95-144.

[10] Carlos Sánchez Silva, Indios, comerciantes y burocracia en la Oaxaca poscolonial, 1786-1860 (Oaxaca, México: Instituto Oaxaqueño de las Culturas; Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca, 1998), 66-69.

[11] See the exhibition catalog for “Goya, His Time, and the Bank of San Carlos: Paintings from the Bank of Spain,” Exhibition at the Federal Reserve Board, October 5-December 4, 1998 (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System).